Translation of the German interview:

YELLO - STELLA - Interview with Boris Blank

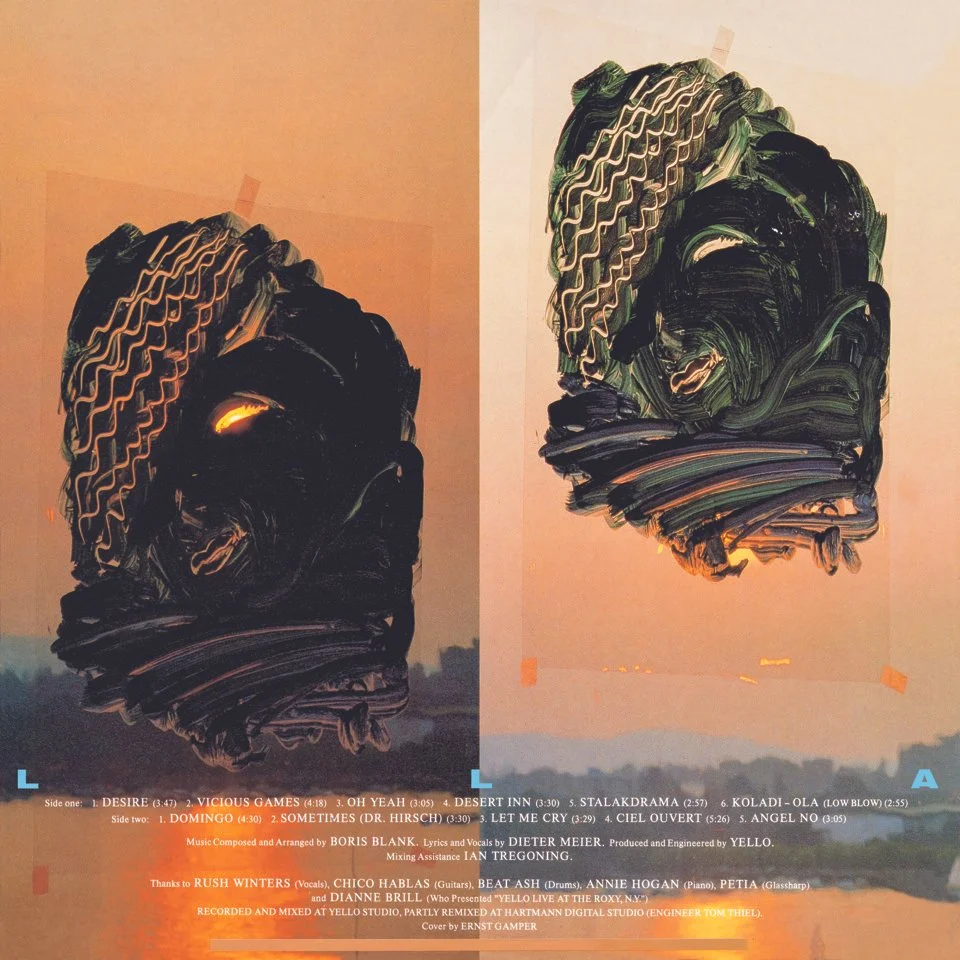

The group YELLO is made up of Boris Blank and Dieter Meier. After the tape release of the album STELLA on April 3, 2024, I was looking forward to the interview with Boris Blank on May 11, 2024 at the HIGH END in Munich. The organization was perfect, Boris was on site shortly after 10 a.m. and was able to make many fans happy with an autograph. There was a huge crowd in front of the Horch House stand. Cameras were held in the air, film and reporter teams were able to catch pictures. My interview with Boris was scheduled for 12 noon. My review https://www.audiotapereview.com/0642024yellostella already contains the interviews with Alex Hefter and Jürg Schopper about the making of the tape project.

Claus: How did the album name STELLA come about?

Boris: That slipped my mind. The most difficult thing is not to make the music, it's more difficult to find titles for the tracks, and then: Which one will be the album title? Dieter Meier would come up with suggestions every two or three days and say: "Boris, I've got it!" I then came up with 20 ideas and we ticked off what didn't work. In the end, a title emerged and it was usually Dieter who came up with the short titles. That was the case with POINT, the last YELLO record, for example. Dieter called from Buenos Aires: "Boris, I've got the title, what do you think of POINT?" I said: "Exactly, that's the one". It was probably the same with STELLA. I don't think it was my suggestion. STELLA means star in Italian. It's a beautiful name that looks good and sounds very nice phonetically and you can do a lot with the typography.

Claus: What thoughts did you have about the sequence of the titles?

Boris: That's my department. I've been making the music for YELLO for more than 45 years. The criteria are tempi, key and ultimately choreography and dramaturgy. How does that build up? On YELLO's last albums, I always shifted the pieces according to feeling, one there, the next there. That's how the album came together in the end. It's interesting that Oh Yeah wasn't actually intended for this record. The story of Oh Yeah is that our manager Ian Tregoning went to America from London where he had friends in the music business. He was asked by the music supervisor for "Ferris Buller's Day Off" if he knew anyone who had a track for a key part in the movie. Ian Tregoning played the track and John Hughes, the director, said: "That's exactly the point." As a result, the track became very well known in America. Since then, Oh Yeah has been requested again and again for films and commercials. A documentary film about the cult status of Oh Yeah will premiere in the USA this fall.

Claus: You said the following about the attempted digital production of STELLA: "All the balances were wrong and the dynamics were lost, so I made a lot of remixes in Zurich to save the album". That sounds like a disaster. What couldn't digital technology do back then?

Boris: We were in a digital studio near Nuremberg in Germany. I had brought the basic ingredients for the mix. We had transferred the multitrack tapes to digital. We thought that was the future and had mixed it together. It wasn't just the digital, but also the unfamiliar acoustics in this studio. I had no reference like in my studio to know how it should sound. When I returned to Zurich with the mixes, I was disappointed. The music was flat, it had no depth, no transparency. So it was more of a mixing issue than the relationship to the digital era back then. I remixed all the tracks except Angel No with my analog equipment until they met my expectations.

Claus: Many musicians leave the sound aspects of their albums to the sound engineers. What drives you to take these aspects into your own hands and work out the good sound as the main feature alongside the music, which thankfully still pays off today?

Boris: First of all, it's the great joy of creating music. The best time is to be hermetically isolated in the studio. I'm like a monk in seclusion. I'm as happy as a child when something new is created. I don't work like a musician. I'm more like a sound painter on a journey of discovery, putting something together from sound colors. When a contour emerges in this sound structure, I can see where the journey is going and am very often surprised at how the piece sounds in the end. It's never what I would have imagined. Then comes the administrative work, the hard work, which involves a lot of discipline. It's sorting the frequencies so that there is no interference, for example. My wish from the very beginning was to mix the music in such a way that it is separated from the frequencies in such a way that a transparency is created that provides a perspective so that you can enter into these sound structures. For example, you can see a horizon far ahead in the sound image, which is represented by a string or something similar. People say about this work that I'm a perfectionist. I am, but only in this process. Otherwise, I'm a chaotic person when it comes to music. I'm like a squirrel that buries its nuts, I have to help myself a little bit from everywhere. I have my folders on the computer and know exactly where I can find prefabricated fragments of sounds from which I then help myself.

Claus: How did you manage to get the noise under control with the analog systems back then?

Boris: That's a very interesting question. I always struggled. On the one hand, it's good if a certain live situation is audible and if you can also carry a little "dirt" on the tapes in the broadest sense. I then had Dolby SR noise reduction systems for 48 channels. I realized that this noise reduction is good for certain sounds or instruments, but not for a base drum, for example, which has an incredibly sharp attack. The gate of the system doesn't close fast enough. I complained about this to Dolby in England. I was told to send the example and they would send it to Ray Dolby himself in California. Ray had to admit that the kick of the base drum, the dynamics, were not being picked up. The electronics were lagging behind. Ray then sent me two modified channels to try out, but that wasn't it either. Then I got a bit further away from Dolby SR and recorded analog again, but worked very cleanly. Then came the digital era with Logic from Imagic and the Atari computer. Digital recording meant that there were no more unpleasant noises. There were still artifacts, but they played less of a role, you could get them under control.

Claus: In 1985, we had a lot of discussions among friends about how you managed to get the voices right? Were they also pitched upwards, i.e. turned from a male voice into a female voice? What equipment was used for this?

Boris: Dieter's voice on Oh Yeah was pitched down very slightly with an Eventide Harmonizer. It didn't have to be much, he can sing very low. With I love you it was me. I corrected my voice up three semitones and it sounded like a woman's voice.

Claus: Which tape recorders did you work with for the productions during this time?

Boris: I experimented with a Revox A77, which was already in my parents' house, and created my first sound collages, i.e. playbacks and recorded them again. With the variable speed, I had discovered the creation of acoustic spaces. I was able to create a real echo using feedback. The result was as fascinating as an echo in the Swiss Alps. I had also created fantastic spaces with Indian bamboo flutes. It sounded like the Taj Mahal. I bubbled with a straw in a kettle. It sounded like a swampland. Then came the wonderful time with a 4-track Teac machine and later, when I got together with Dieter Meier, it was an 8-track Otari. Next came two Otari with 24 tracks in the studio and a Teac mixer with 48 channels.

Claus: Did you use equipment from your analog production days on the current album RESONANCE?

Boris: I still have a relationship with one device: it's the Arp Odyssey synthesizer. I also have a Roland vocoder. Apart from that, I've always been a person who was musically involved in new technology.

Claus: Will there be a tape release of RESONANCE?

Boris: I think so, of course.

Claus: Thank you very much for the interview.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)